Today I’ll talk a little bit about frontend (don’t be mad 🥺🙏). First, I’ll briefly introduce what WebAssembly is, and then how it relates to Go. I’ll probably write more about this subject, but first I want to make this introduction to get everyone on the same page. The idea of this blog is not to post gigantic articles, but smaller ones every week (I’ll try my best 😉) that can talk to each other.

I presented on this subject at GopherCon Latam 2024. If you prefer video and understand Portuguese, here is a link.

The history

Grab your popcorn, it’s history time!

Before WebAssembly was born, a wild battle was raging on the internet. The year was 2010, and Google and Mozilla were deciding what the future of the web would look like.

In 2008, Google created the Native Client (NaCl), a way to run a subset of native machine code (x86 for instance) in a sandbox in your browser. The code ran at great speed, but it couldn’t access the existing Web API because everything was running in a separate process, so you had to deal with a plugin API, like Flash used to do.

Mozilla started a new project called Emscripten in 2011, a compiler from C and C++ (or any LLVM-supported language) into JavaScript (at that time). It’s web-friendly because, at the end of the day, it’s JS and can communicate with the Web API. But it’s bad for the same reason, because it’s JS 🤪, so it’s slow. Then they decided to create asm.js, a subset of JS with the capabilities of some AOT (Ahead of Time) compilation, more reliable and consistent optimizations than the JIT (just in time) compilation. This enabled asm.js to run faster than normal JS code, but it was still JavaScript, so it couldn’t compete with binary code.

In 2013, Google and Mozilla put their differences aside and started working together, collaborating, and in 2015 NaCl and asm.js had a baby called WebAssembly:

- It can interact with the DOM and Web API

- It’s not JavaScript; it’s binary code that runs in a VM (to be portable)

If you want to know more about this story in detail, take a look at this presentation by Alon Zakai, the creator of Emscripten and co-creator of WebAssembly.

WebAssembly

When we break the term into Web and Assembly, we might think it is a way to run Assembly on the Web, in your browser, right? That’s (almost) right; it’s actually a low-level assembly-like code.

WebAssembly (abbreviated Wasm) is a binary instruction format for a stack-based virtual machine.

This is quite enlightening. Now we know that WebAssembly is a programming language (a low-level one), so it means you can write it, but it’s not meant to be written by you (usually). It was made to be compiled from other languages like Go, Rust, C, etc.

And the idea here is not for WebAssembly to kill JavaScript (I wish 😅), it’s for them to work together, to be complementary. You can take advantage of JS flexibility to work with your webpage’s common usability, simple components, texts, inputs, etc., and leave the hard work to your WASM code when you need to deal with complex algorithms, CPU or GPU-heavy processes.

WebAssembly is especially useful for porting games to your browser; Unity uses it to export games for the web. Tools like Figma took advantage of WASM, writing their code in C++ and running close to native speed in the browser.

But it doesn’t stop there; WASM is being used for much more. Although it was conceived with browsers in mind, at the end of the day it runs on a VM—the browser just happens to have a runtime that runs it, like V8 on Chrome.

That’s when WASI (WebAssembly System Interface) comes into play in 2019, a standardization of APIs for WebAssembly to deal with systems outside the browser, like network stuff and filesystems. In a nutshell, you can run your CLIs and backend services as WASM binaries. To do this, you need a runtime, and there are lots of options like wazero and wasmtime.

You can even have one of these runtimes inside your Kubernetes cluster and, instead of using containers, you can run WebAssembly binaries or run WASM files inside your containers. There’s a CNCF project called wasmcloud that can orchestrate your WASM services. It’s still uncertain what the future holds; some say WASM will replace containers as we know them because they’re fast to start, smaller than container images, and secure because they run isolated from the host in their own sandbox. But at the same time, WASM code is limited to the functionalities standardized by WASI, and not all languages have compilers to WASM.

Another use case that I really like is tools where you need SDKs for different languages. You can create the core functionalities in Rust, for example, and compile to WASM. Then, instead of recreating the whole SDK in different languages, you just create the “interfaces” for that specific language that call all the WASM logic from that binary you compiled. A good example is some of the Flipt’s SDKs like Go, JavaScript, and React. They have a pretty interesting article about this choice.

Hence the title of the post, it’s like a common tongue for the programming languages to communicate between them and with the web itself

Go + WebAssembly

I hope you now know at least a little bit about what WebAssembly is and what it’s capable of. Now let’s talk about Go’s support for WebAssembly.

It was introduced experimentally in 2018 with Go 1.11, meaning it got a WASM compiler. This port evolved, and in 2023 WASI support was introduced experimentally in Go 1.21. And if you pay attention to the release notes, it’s common for some new Go versions to have a WebAssembly section with some improvements, like binary size.

Talking about the binary size of WASM, usually Golang ones are bigger and slower than Rust WASM binaries, for instance. This is due to having to include all the goroutine runtime, garbage collector, maps, and other Golang stuff into it. Like I said, it has improved a lot. Another thing that could help reduce size and improve performance would be targeting WASM runtimes with garbage collector extension. Since 2023, Chrome already supports WASM GC by default. This way, the Go compiler wouldn’t need to include the GC in the binary, so it would be smaller…

But we have an option for smaller WASM binaries using Golang; it’s called TinyGo, an embedded systems and WebAssembly-focused compiler based on LLVM, implementing lots of optimizations, removing some Go runtime capabilities, not supporting some Go standard libraries, and using a different minimal garbage collector.

What should you use for WASM? It’s up to you and your project. If you want to port already written standard Go code to WASM, maybe it will be better to just compile it using the Go tool. If it’s a new app, simpler and that must be as small as possible, TinyGo is the way. If you have the chance, test both and compare them; performance may vary depending on the tasks you are dealing with.

Hands on

For these examples, I’m using Go 1.24.5 and TinyGo 0.38.0:

Let’s do a simple example just to help you understand things a little bit more. I’ll create a simple Go code just to print “WebAssembly” in a main.go file. The idea here is for our browser to print this message at the end:

package main

func main() {

println("WebAssembly")

}

The Go tool already has the built-in capability of compiling to WASM. In order to compile it to run in our browser, we need two steps. I’ve created an assets folder that will contain all our files to be served by our file server. First, build our binary:

GOOS=js GOARCH=wasm go build -o ./assets/main.wasm

Second, we need a supporting file (it’s already on our machine as soon as we install Go) that allows us to communicate with our JavaScript code, so:

cp "$(go env GOROOT)/libs/wasm/wasm_exec.js" ./assets

Then we create an html file that will import both files with the following content:

<html>

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8"/>

<script src="wasm_exec.js"></script>

<script>

const go = new Go();

WebAssembly.instantiateStreaming(fetch("main.wasm"), go.importObject).then((result) => {

go.run(result.instance);

});

</script>

</head>

<body></body>

</html>

Lastly, I will create a simple Go file server pointing to our assets folder:

package main

import (

"net/http"

)

func main() {

http.ListenAndServe(":8080", http.FileServer(http.Dir("./assets")))

}

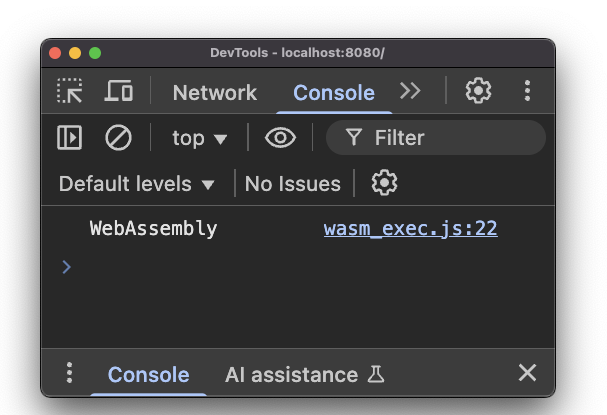

And as expected, the console printed our message:

Congratulations, you have just run your first Go code in the browser (if you have never used WebAssembly with Go before, of course 😄).

I’ve talked about TinyGo, so let’s compile our WASM file with it. The main.go will not change, nor will our server or HTML. The only difference here is the build commands:

GOOS=js GOARCH=wasm tinygo build -o ./assets/main.wasm

And the JS support file is located in a different place. The location might be different depending on your OS and how you installed TinyGo, but in my case I installed it using Homebrew, so the command to copy the file is:

cp "/opt/homebrew/Cellar/tinygo/0.38.0/targets/wasm_exec.js" ./assets/wasm_exec.js

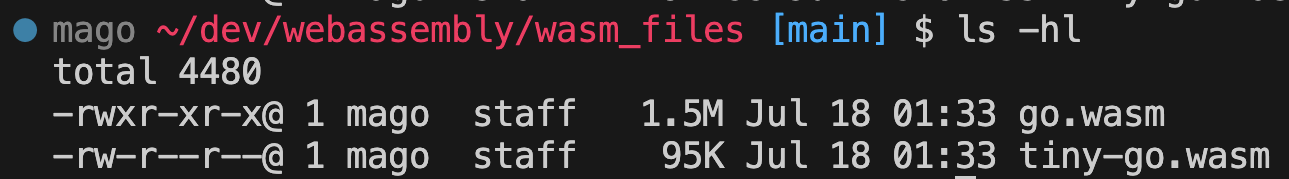

The result is the same, but the file size is quite different. Renaming them to go.wasm and tiny-go.wasm:

We can see that the TinyGo one is only 95K and the Go one is 1.5MB, which means 15 times bigger 😱. This is not a good example to dive into performance (maybe in another post), but choose wisely 🧙♂️

Real world example

Ok, this is interesting, but it’s just “Hello World” code—not so exciting, right? Remember I talked about how WebAssembly is interesting for porting games to the web? Well…

At GopherCon 2024, where I presented a WebAssembly talk, there was another speaker from Varginha, a Brazilian city known for the most notorious alien appearance in Brazil, Matheus Mina (“seus cabelo é da hora”, as Mamonas Assassinas would say 😂). We were talking in the VIP room, and he was developing a game using Ebitengine. It’s that game where you have to order the numbers by sliding the pieces. We talked, and I decided to port his game to the web, so I forked it, added touch screen support, compiled it to WASM, and uploaded it to my website using Github Pages.

Here’s the code and the game can be played at this address.

What about you? Did you know about WebAssembly? Have you worked with it before? What are your thoughts on the future of WASM and its integration with Go?